“Unimaginable discovery”: Long-lost da Vinci painting of “Savior of the World” to fetch at least $100 million at auction. “Standing in front of that painting was a spiritual experience. It brought tears to my eyes”

Originally Published in the Washington Post

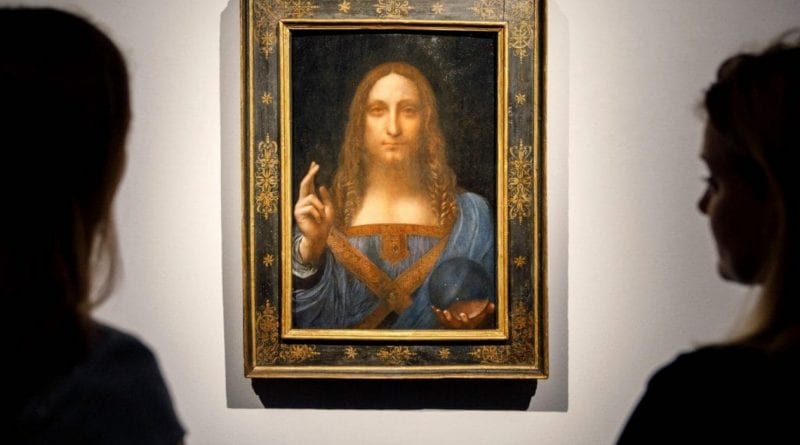

When Nina Doede first saw Leonardo da Vinci’s long-lost painting “Salvator Mundi” — Latin for “Savior of the World” — she was in awe.

“Standing in front of that painting was a spiritual experience. It was breathtaking. It brought tears to my eyes,” Doede, 65, told the New York Times.

She was one of 27,000 people, including Leonardo DiCaprio, Alex Rodriguez, Patti Smith and Jennifer Lopez, who flooded into viewing halls in Hong Kong, London, San Francisco and New York for a chance to glimpse the highly anticipated treasure during the past few weeks.

On Wednesday night, someone will get the opportunity to own the painting, the only da Vinci in a private collection, when it goes up for auction through Christie’s in New York City. It’s guaranteed to sell for at least $100 million, meaning the auction house will make up the difference if it goes for less.

[wpdevart_like_box profile_id=”ministryvalues” connections=”hide” width=”300″ height=”125″ header=”small” cover_photo=”show” locale=”en_US”]

The small piece depicts Jesus raising his right hand in blessing and holding a crystal orb, meant to represent the world, in his left. It’s one of some 16 known surviving paintings — including the “Mona Lisa” — by da Vinci, the master of the Italian Renaissance. The others are scattered throughout the world’s museums.

Billed by the auction house as “The Last da Vinci,” the painting spent centuries in obscurity until it was rediscovered in 2005 and underwent a six-year restoration and verification process.

Since then, it has attracted awe, scrutiny and, inevitably, a lawsuit.

Da Vinci painted it in the early 1500s, and it quickly inspired a number of imitations. Over the years, art historians have identified about 20 of these copies, but the original long seemed lost to history.

At one point, it was part of the royal collection of King Charles I of England. It disappeared in 1763 for nearly a century and a half. In 1900, Sir Charles Robinson purchased the painting for the Cook Collection in London. But by then, it was no longer credited to da Vinci but to his follower Bernardino Luini.

In 1958, the collection was auctioned off in pieces, with “Salvator Mundi” going for a mere 45 pounds, which translates to about $125 today, CNN reported.

Then it dropped off the grid for another 50 years until resurfacing in Louisiana in 2005. There, for $10,000, New York-based art collector and da Vinci expert Robert Simon and art dealer Alexander Parish found and purchased it, the New Orleans Advocate reported.

At first glance, Simon thought it was just another copy of the famed painting.

“It was a very interesting painting but it’s not something I looked at and thought, ‘Oh my god, it must be a Leonardo,’” Simon told CNN. “The whole idea that it might be by him was almost an impossibility; it’s kind of a dream.”

The piece was thick with overpaints, meaning artists had added paint to the existing image over the years as a means of either modernizing or improving it, likely to cover up chipped areas in the original.

Dianne Dwyer Modestini, a professor of paintings conservation at New York University, set about carefully restoring the portrait — which was still believed to be a copy — in 2007. She started chipping away at the varnish and overpaint obscuring the original, the beginning of a process that would take six years.

A strange feeling overtook her as she removed the first layer. For one thing, Jesus’ curly hair looked strikingly familiar.

“I was looking at the curls and St. John the Baptist at the Louvre, who has this huge head of massive ringlets and they are exactly the same,” Modestini told CNN.

It began dawning on her. The last da Vinci painting discovered and verified was “Benois Madonna” or “Madonna and Child with Flowers” in 1909.

“My hands were shaking,” Modestini told Christie’s. “I went home and didn’t know if I was crazy.”

A series of tests proved she wasn’t.

One of the key pieces of evidence was found via X-ray, which revealed what’s called a pentimento, a trace of an earlier painting beneath the visible one. It showed that Jesus’ right thumb was originally positioned slightly differently. But while working on the piece, da Vinci must have changed his mind and painted over it — the thumb was moved to the position in which it appears today.

“If you’re making a copy of a picture, there’s no way you’d do that,” British art critic Alastair Sooke said in a video for Christie’s. “It wouldn’t make any sense.”

That’s especially true when considering that “in all the copies of the painting, [the finger] follows the finished position,” as Simon told National Geographic.

There were other clues as well, History.com reported. It was painted on walnut in “many very thin layers of almost translucent paint,” like other da Vinci pieces from the era. Infrared light showed that the painter pressed his palm into the wet paint above Jesus’ left eye to smudge the colors, a technique da Vinci favored called sfumato blurring.

In 2011, the art community reached a consensus: This was a bona fide da Vinci.

“It’s the most unimaginable discovery of the last 50 years,” London-based art dealer Charles Beddington told the New York Times. “A painting by Leonardo is one of the rarest things on the planet. You can’t imagine it’s ever going to happen again.”

Or, as Simon told CNN, “This is not a little ripple in a pond, this is like a boulder,”

The painting made its public debut at London’s National Gallery in a 2011 exhibit titled, “Leonardo da Vinci: Painter in the Court of Milan,” where it “became one of the most talked-about pictures in the world,” as the New Yorker wrote.

Not only that, but it was one of the more expensive paintings in the world.

A consortium of dealers including Simon, Parish and Warren Adelson sold the painting in 2013 for $80 million to a company owned by a Swiss businessman and art dealer Yves Bouvier, Bloomberg reported.

Bouvier then flipped the painting the next year, selling it to Russian billionaire Dmitry Rybolovlev to the tune of $127.5 million — an almost $50 million markup.

Rybolovlev allegedly learned of the price difference from the New York Times, prompting an ongoing legal battle filled with suits and countersuits between Rybolovlev, Bouvier and Sotheby’s, which was the intermediary in the original sale to Bouvier.

The ongoing dispute has been dubbed “The Bouvier Affair.”

At Wednesday’s auction the painting will likely again switch hands. If it merely sells for the guaranteed $100 million, Rybolovlev will lose $27.5 million from the deal.

Either way, it will be a member of a rare club of paintings that recently sold for more than $100 million. As Artsy noted:

An untitled Jean-Michel Basquiat painting sold for $110.5 million in May; in 2015, Pablo Picasso’s Women of Algiers sold for $179 million and an Amedeo Modigliani nude sold for $170 million; and in 2013, an Andy Warhol car crash painting sold for $105.4 million.

Not everyone thinks it’s worth quite that much.

“Even making allowances for its extremely poor state of preservation, it is a curiously unimpressive composition and it is hard to believe that Leonardo himself was responsible for anything so dull,” Charles Hope, an emeritus professor at the Warburg Institute at the University of London, wrote of the piece.

Whether bidders agree with Hope or not will be proven tonight.